Being in prison reminds me of a quote by Pascal, the 16thC french mathematician and philosopher. I don't have access to the internet or other reference to verify the exact quote so this is the paraphrase:

"Man is the most blessed of creatures because he can contemplate his existence; he is the most miserable of creatures because he can contemplate a better existence than he has."

[Note: Even with access to the internet, I have been unable to verify this quote from Pascal... or anyone else for that matter. Hmmmm, that's strange. I can't believe I just made it up.]

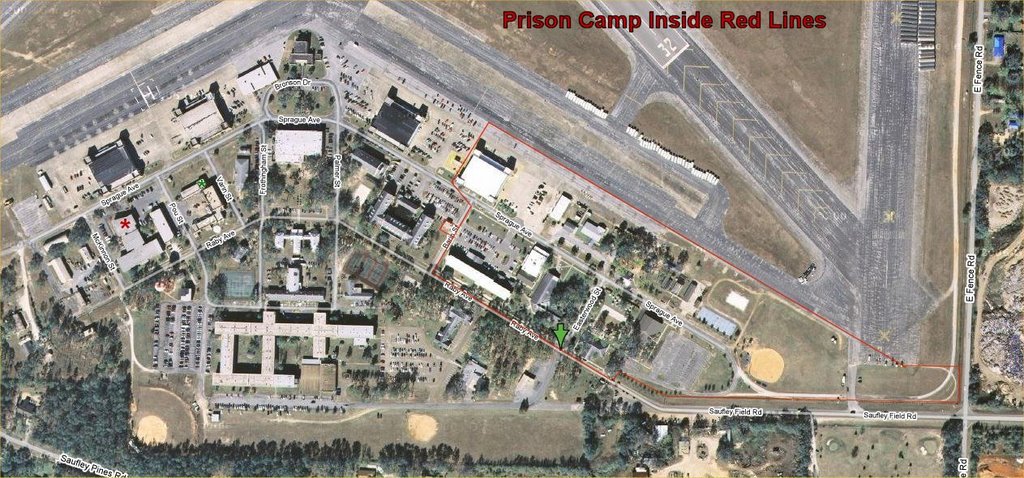

Prison, at least FPC Pensacola, is not uncomfortable. It is an inconvenience. If I was a dog, life would be great (except for the absence of female dogs!) My physical needs are basically taken care of; there is no real outward stress on my life.

But I am not a materialist -- there is more to life than physical matter and physical needs. I simply don't have enough faith to believe that human personality, self-consciousness, and the "soul" could have evolved from impersonal matter (it is hard to see how, if entropy is one of the laws of the universe, that personality can derive from impersonality); it had to come from pre-existent ultimate Personality... God.

Pascal's [or someone's!] point is an indirect argument for the existence of God and of a "world" that man is ultimately intended to be a part of. The nagging awareness that there must be more to life is, in a sense, an argument that there must be more. Otherwise, where would the hunger for "meaning" come from. (I believe that CS Lewis tried to make a similar argument. [But don't quote me on that one either!!]) I am not a trained philosopher so I haven't studied the argument in detail but is is intriguing to me.

Prison really intensifies this "blessed-miserable" tension. Your basic physical needs are supplied for you, allowing for plenty of time to contemplate a "better" existence. (Oftentimes I think in the "real" world we are so busy meeting our physical needs, that we never slow down enough to recognize our spiritual needs, let alone address them.) Failure to resolve this tension can result in a depressing sense of ennui (I love that word); you can see this in the eyes of men who have become institutionalized.

At orientation, the chaplain, a Catholic priest, made the observation that inmates who sought strength from a "Higher Power" handled their prison experience much better than those who didn't. In other words, they had resolved this tension. It is easy to spot these inmates also. They do not view their prison experience as lost time; they recognize they are on God's time.

In some cases, they view their sentence, even if grossly harsh (as is the case with most federal sentences), as a blessing -- remembering the famous quote of Joseph in Genesis (after being unjustly sold into slavery yet rising to become assistant to the Pharaoh): "What man meant for evil, God intended for good." (Gen 50:20) The parallel is not perfect because of course Joseph was completely innocent, but this perspective allows an inmate to let go of any grievance they might have about the injustice of their harsh sentence (while still acknowledging his basic guilt and responsibility) and believe that God can turn it into good.

The hope for a better existence, whether in this life or the next, is what provides the motivation to take steps that will promote that end and to endure present suffering. This principle applies to anyone, regardless of their current life situation.

The purely secular man, believing that this life is all there is, acts to maximize pleasure in this world (which is kind of hard in prison!); the Christian acts to maximize pleasure in the next world, while not denying an appropriate role for pleasure in this one. (The Apostle Peter stated that "God gives us all things to richly enjoy.")

Certainly a corollary to this is to hold all "things" loosely. Not only can you not take them with you when you die, but you might have them take from you before you die, as many guys here can testify!

Hopefully, I will use my time here to reassess my priorities and take an inventory of what I own and what owns me.

No comments:

Post a Comment