If you are interested in the background of the case, I encourage you to read the second link above on the TaxProf Blog. I would like to focus on the sentencing issues, in particular the role of "general deterrence."

In Federal Court, sentencing is governed by 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a), which identifies the factors to be considered in imposing a sentence. There are 7 factors but #2 is probably the most important:

The court shall impose a sentence sufficient, but not greater than necessary, to comply with the purposes set forth in paragraph (2) of this subsection

(2) the need for the sentence imposed—

(A) to reflect the seriousness of the offense, to promote respect for the law, and to provide just punishment for the offense;

(B) to afford adequate deterrence to criminal conduct;

(C) to protect the public from further crimes of the defendant; and

(D) to provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner;

These cover the classic elements of retribution (just punishment), specific deterrence (including rehabilitation and incapacitation), and general deterrence (that is, discouraging others from committing the same offense).

Of these, I think it is indisputable that the priority should be

1. Punishment -- the sentence should fit the crime

2. Specific Deterrence -- the sentence should discourage the criminal from repeating the offense. This can be accomplished by incapacitation (e.g. prison) and/or rehabilitation (changing the person).

3. General Deterrence -- the sentence should "send a message" to the community at large in the hopes of discouraging the criminal conduct.

If I had to apply percentages, I would put "punishment" at 60%, specific deterrence at 30% and general deterrence at 10%, although reasonable people can disagree with the weights.

Unfortunately, however, prosecutors completely invert this order. Indeed, the judge in the Wesley Snipes case, in ruling on an earlier motion to dismiss the case for selective prosecution, said:

From a prosecutor's point of view, especially in tax cases, the primary objective in deciding whom to prosecute is to achieve general deterrence.I find this very disturbing. While I understand that, "especially in tax cases," general deterrence may play a slightly stronger role, this judge is suggesting that general deterrence is the primary objective in all cases (but especially in tax cases) for a prosecutor.

Apparently, from this judge's point of view, general deterrence is the Court's primary objective in sentencing. He did not say that, but it is strongly implied. And it is completely backwards.

So this raises a very important question.... actually two of them (maybe more!):

1. What role should general deterrence play for prosecutors in selecting cases.

2. What role should general deterrence play for judges in sentencing defendants (especially if the defendant is a celebrity).

The government's sentencing memo in the Snipes case was very interesting. It is 37 pages long and I encourage you to read it all but especialy Section III (pp. 18-24) on deterrence.

(By they way, I love reading these things -- sentencing memos, court opinions, etc -- especially if they are written and argued well, which this one was, even though I fundamentally disagree with the approach taken by the prosecutors.)

The problem the prosecutors had is that Snipes had been acquitted of all the felony counts and convicted only of the three misdemeanor counts (failure to file tax returns in 3 years). The felony counts have maximum sentences of 5 years I believe (indeed one of Snipes codefendants,. who was convicted on all counts, received 10 years) but the misdemeanor counts have a maximum sentence of only 1 year each so the most the court could sentence Snipes to was 3 years despite the fact that the US Sentencing Guidelines (based on the amount of taxes Snipes did not pay) would have set his sentence to more than 10 years, according to the prosecutors. This is one of the rare cases in which the maximum sentence allowed by law is actually lower than the guideline sentence.

The prosecutors were clearly miffed at the trial outcome for Snipes and were trying to make the case for the maximum sentence given they only had 3 misdemeanor convictions to work with.

They did this in two ways:

This case cries out for the statutory maximum term of imprisonment, as well as a substantial fine, because of the seriousness of defendant Snipes’ crimes and because of the singular opportunity this case presents to deter tax crime nationwide.

First, they focussed on the seriousness of the offense. Certainly, relative to most convictions for misdemeanor "failure to file a tax return" offenses, this one was off the charts. I will not restate all the facts but basically Snipes appeared to underpay his taxes to the tune of several million dollars under the most generous of assumptions:

Even if one considers solely the actual tax loss associated with the counts ofThe guidelines would call for a sentence of 47-63 months at this level of "loss."

conviction, and excludes both the actual and intended loss from relevant conduct, the tax loss for which Snipes is responsible, solely by virtue of the jury's verdict on the three counts of conviction, is several million dollars.

The prosecution believes the losses should however be higher for sentencing purposes if one considers other "relevant conduct:"

For sentencing purposes, the Court is entitled to consider such relevant conduct as it finds by a preponderance of the evidence, even when related to acquitted conduct.What this means is that the court can consider other conduct related to the convicted offenses in determining damages or make other sentencing enhancement choices, even if it involves conduct that the jury acquited.

Acquitted conduct sentencing enhancements occur when a jury finds a defendant guilty of some counts but not guilty of others. The judge, however, in deciding to sentence a defendant can decide on his own, based on a preponderance of the evidence (a much lower standard than reasonable doubt), that even the acquitted conduct is relevant and sentence based on that.

I kid you not. Welcome to the Rabbit Hole, that strange and bizarre world of federal sentencing.

If you asked someone on the street if a defendant could be sentenced for conduct he was acquitted of, he would look at you like it was a trick question. Of course not, right? Wrong.

You could be acquitted on 9 out of 10 counts and be sentenced as if you were convicted of all, limited only by the statutory maximum for the count you were convicted of.

This subject deserves a totally separate article but for those who want to preview it themselves, check out this Strong commentary on acquitted conduct sentencing, including a reference to a great article brilliantly titled "Not guilty. Go to jail."

Nonetheless, had the prosecutors simply stuck with actual damages and the seriousness of the offense, they had a very strong argument, on that basis alone, for sentencing Snipes to the maximum.

But they did not stop there, nor did the court apparently.

They cited the "singular opportunity this case presents to deter tax crime nationwide" because this was "the most prominent tax prosecution since the 1989 trial and conviction of billionaire hotelier Leona Helmsley."

Furthermore, "(t)his case accordingly presents the Court with a momentous opportunity to instantaneously increase tax compliance on a national scale."

Other selected quotes from the government's sentencing memo:

The fact that Snipes was acquitted on two felony charges and convicted “only” on three misdemeanor counts has been portrayed in the mainstream media as a "victory" for Snipes.In effect, the government argues that Snipes should be especially punished because he is a celebrity and because of press coverage and public perceptions over which he has no control.

The troubling implication of such coverage for the millions of average citizens who are aware of this case is that the rich and famous Wesley Snipes has “gotten away with it.” In the end, the criminal conduct of Snipes must not be seen in such a light, or else general deterrence -- “the effort to discourage similar wrongdoing by others through a reminder that the law's warnings are real and that the grim consequence of imprisonment is likely to follow” -- will not be achieved.

Snipes’ acquittal on the tax conspiracy and false claim counts has been perceived in those circles as a vindication of anti-tax theories and a "win" that will attract additional converts into their movement.

There is, unfortunately, a profound need to discourage others from emulating Snipes' criminal tactics against the IRS.

General deterrence in this case depends upon the public seeing some consequence for Snipes beyond a vague promise to make amends with the IRS.

That is the biggest argument against general deterrence in general and especially in this case: it treats the defendant differently than everyone else. Snipes is not receiving "equal justice under the law." The prosecution is all but conceding that if Snipes was just someone like you or me, then the sentence should not be as harsh.

Basically, however, in this case, they want to cut his head off and stick it on a pole to the entrance to TaxProtesterLand to let everyone know what happens to tax protesters.

This is an illegitimate application of the law and certainly an illegitimate motivation for prosecutors to select cases based on celebrity-status in order to leverage the publicity associated with that individual. (This was also a criticism I also made of the government in the Michael Vick case.. he was singled out and punished more harshly because of who he was.)

The only reason Snipes became a public face for the tax protester movement is because the government made him the public face by singling him out for prosecution, rather than some of the leaders in the movement who, unknown outside the movement, would not generate the publicity that a Snipes trial would. This was clearly a calculated strategy.

To some degree, that strategy blew up in their faces when Snipes was acquitted of the most serious charges, leaving them to pick up the pieces with this recommendation for the maximum sentence on the convicted counts.

As I have said, I think a strong argument could be made for the sentence Snipes received based solely on retribution and specific deterrence factors. However, making general deterrence the centerpiece of the argument is very troubling.

--------------------------------------------------------

By the way, I knew a tax protester in prison: Ward Dean, MD. Ward is a 65 year old man (doctor and Naval Commander) that became enamored with the tax protester movement late in life for reasons I don't totally understand.

Basic facts of his case can be found here although he has his own site that discusses his medical as well as tax beliefs and legal case in great detail. Trust me, he is not repentant. Indeed, he has all the energy of a true believer and continues to fight his case. We chatted frequently and he gave me books as well as medical advice (he is well-versed in anti-aging medicine).

He was convicted in December, 2005 and received an 88-month sentence (twice that recommended by the guidelines) in July 2006. He reported to prison in late 2006, several months before me and is not scheduled for release until 2012!!

He is a perfectly decent guy although, as I stated, definitely a true believer. He is very opinionated but slightly eccentric. He will debate anyone who will listen to him on these subjects.

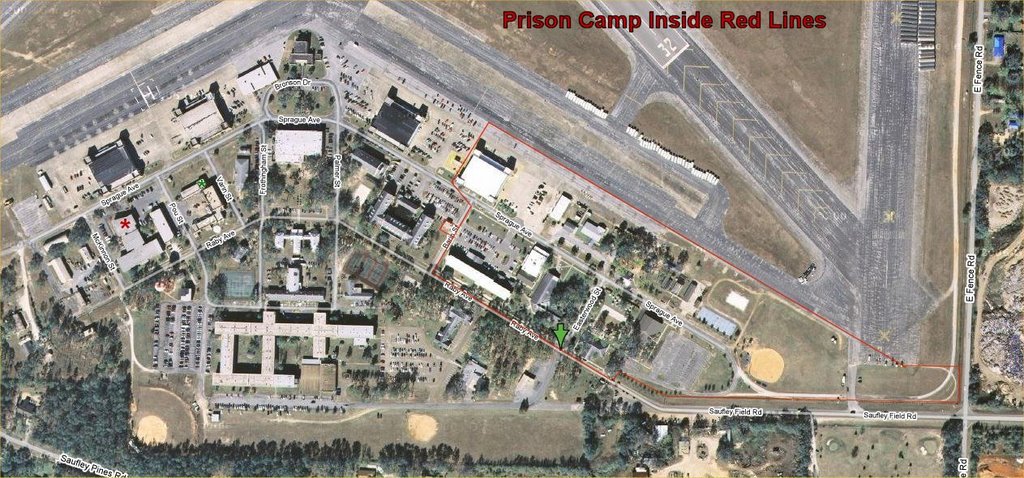

Ironically, for a while, his work detail had him doing groundskeeping within eyesight of the office where he used to practice medicine as a Naval Commander! Talk about a change of circumstance.

Regardless of the merits of the tax protester movement, it takes a special person to sacrifice his liberty for a cause. I could count on one hand the issues or principles for which I would be willing to go to prison in defense of; actually, maybe on one finger.

And taking on the government over the legality of our tax code would definitely NOT be one of them!

God bless you Ward.. and good luck. I respect your determination but I'm not ready to join you as a martyr for the cause.